Letters in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice offer a deeper look into the core of Austen’s characters, as the letters act as pseudo-diaries for each character, portraying events in a light which the narration cannot capture due to the lack of omniscience in the text. Through the use of comprehensive word clouds of each of the full letters sent between characters in the novel (excluding small notes), the character description in the narration of the novel and the actions of the characters can be juxtaposed with the main ideas and words of the characters’ letters. This demonstrates whether the characters’ consistent actions really portray who they are, or if something else lies beneath their surface.

Word clouds make the best representation of the characters because even single words are so powerful, both in secondary character development (narration) and direct character action (speaking or dialogue). In pulling only the key words and ideas from the letters each of the characters writes, the key aspects of that characters core come to the foreground. Using this tool, one can remove the unnecessary, superfluous fluff from the outside of the character profile, and dive into the deeper aspects of the character; in this case, the letters used to make word clouds are considered directly indicative of the character who writes them.

The first letter sent from one character to another is Mr. Collins’s letter to Mr. Bennet, announcing Collins’s impending visit to Longbourn. Textually, Collins appears to be a rather uptight and pompous man, unafraid of continuously and relentlessly milking his relationship with the great and most high Lady Catherine de Bourgh. In his letters, Mr. Collins essentially puts forth the same front (though possibly more pompous and cocky). Of the 371 words in Mr. Collins’s first letter, some of the most common are “duty,” “lady,” “clergyman,” and “Catherine.” Clearly, Collins’s main goal in this letter is to show off his newly acquired status – more than introduce himself to the family, he wants to introduce his position, and though he’ll take over the Bennet estate when Lizzie’s father dies, Collins wants to give the impression that he cares whether the girls get any share in the estate after their father dies. Collins’s second letter (again to Mr. Bennet) doesn’t delve any deeper into his character – obviously a very shallow one at that. The 349-word letter features the words “dear” and “daughter” among the most common, with “Catherine” and “Collins” (in reference to his wife) also on the list. Once again, Collins has demonstrated through his letter that the pompous outside continues on to the inside as well. This time, Collins’s focus leans towards the new acquisition of his wife, and the loss the Bennet daughters have experienced following Elizabeth’s rejection of Collins’s proposal as well as the heinous grievance endured due to Lydia’s indiscretion. Collins becomes extremely patronizing, as the words “dear” and “sir” would suggest. Evidently, not only does Collins represent the single most shallow yet regularly featured character in his dialogue, his letters do little but to reaffirm his completely static character. In this case, the letters tell us what we would have already known.

Mr. Edward Gardiner, the Bennet girls’ uncle, writes letters that give new light to his character. Though we don’t see very much of Mr. Gardiner, this letter helps us to understand a soft spoken character with relatively little page-time. In the text, Mr. Gardiner seems to be a fairly nice man, without much to say or any outstanding character motivations. His letter tells a slightly different story. Mr. Gardiner seems to be a very family-oriented person, committed to making sure everyone in his family is informed as to the current situation, and safe in any and all situations which he can exact control over. All of the most common words in his letter (“niece,” “hope,” “send,” “married,” “particulars”) have to do with the specifics of Lydia’s situation – he wants the family to know exactly what the situation is even though none of them can be there. The same is true for Mr. Gardiner’s second letter. Once again, Mr. Gardiner’s rather introverted character is brought to light. Mr. Gardiner’s demonstrates that his greatest concern is ensuring that although Lydia may not have married into the best situation, she will still have the best possible life. This includes Mr. Gardiner doing everything he can to ensure that Wickham’s credit is clean, as the major words, such as “assurances,” “hope,” and “creditors” would suggest. In this instance, Austen does not as much contradict the character’s presence in dialogue and action as much as actually give the character a personality. Austen’s reluctance to really drastically change anything from the character to the letter demonstrates that keeping the family seem as stable (or, from another view, completely unstable) as possible. Something must remain constant amid the change surrounding Lizzy’s life.

Obviously, Lydia does not have the same consciousness for others that her sisters have; her letter mostly revolves around Lydia and what Lydia has done, is doing, and is feeling, and how she thinks everyone else will react to her situation. This is most likely a result of how her mother brought her up – to think of marriage and nothing else. In her second letter, Lydia once again demonstrates her selfishness isn’t purely a surface matter, but a deep characteristic of her most basic form. Even when her older sister is about to me married, Lydia’s letter focuses more on her own life and husband than congratulations for her dear sister. Where Collins’s letters build a breadth of pompousness, Lydia’s do the opposite – reveal the depth of her narcissism. Again, Austen writes the core characters with a measure of consistency; nothing truly surprising comes to light. However, it is important to note that some people really dislike this consistency in Austen’s work. For example, Ralph Waldo Emerson thought that her work was “sterile in artistic vision.” Clearly, the consistency in characters and plot didn’t please everyone (7 People).

Mr. Bennet sends one letter of which Austen reveals any of the text, and in its entirety has 46 words, and approximately one crap-ton (equivalent to 16 bucket loads) of sass. This letter sums up Mr. Bennet to a tee. He doesn’t mess around, he likes to be simple and quick, and if he can throw in a little sarcasm and sass somewhere, it’s all for the better. Truly, Mr. Bennet’s transparency stands as one of the most undeniable truths of the novel. In this case, Austen stays completely true to the character as portrayed in social interaction in the novel. Mr. Bennet doesn’t deal with anyone else’s baggage.

This letter, from Jane to Lizzy, very clearly illustrates the depth of feeling which characterizes Jane. The major words in her letter have to do with a feeling of anxiety, and are often related to her being the older sister, and feeling a measure of responsibility for her family’s and her own situation. She often tries to explain away others’ actions, and see the best in any given situation. None of the major words in any of Jane’s letters have anything to do with how Jane herself fares, but pertain to other people in the family. Jane’s letters have everything to do with Jane ensuring that everyone else has what they need. Jane generally forgoes telling Lizzy how she (Jane) is, and instead makes sure Lizzy is fully up to speed on recent events, as opposed to Jane venting her feelings to Lizzy. Everything revolves around everyone else for Jane, nothing revolves around Jane herself. As compared to Jane in the text, this actually is a little reversed. In speech, Jane is slightly more willing to talk to Elizabeth about her feelings in certain situations, although she almost never will with anyone else. However, during actual conversation Jane also spends a lot more time finding out about Lizzy’s feelings. Austen most likely spends more time worrying about Lizzy in Jane’s letters because in an actual conversation, Jane would spend much more time talking about Lizzy than herself.

Mrs. Gardiner often speaks up more than Mr. Gardiner, and for the most part seems to be a very caring aunt – possibly the one adult female role model in Jane and Lizzy’s lives who cares for their feelings rather than their being married. Her letter surely confirms that her personality in her small words and actions is indeed true. Though Mrs. Gardiner was not supposed to tell of the events that transpired around the time of Lydia’s marriage, she tells Lizzy anyway, just because Mrs. Gardiner knows that Lizzy is extremely eager to know the details, and just how much her family owes Mr. Darcy. In text, this is also the case. Once again, Austen goes out of the way to demonstrate that nothing has ever truly shaken Lizzy’s life up. Though dysfunctional, her family is constant, which makes the events of the novel that much more extreme. This idea is one of the many beauties of the novel, as Sir Walter Scott wrote in his journal about Austen’s work, “That young lady had a talent for describing the involvement and feelings and characters of ordinary life which is to me the most wonderful I ever met with” (Jane Austen’s Art). The absolute normality of the characters and the novel is what makes Austen’s storytelling so fantastic.

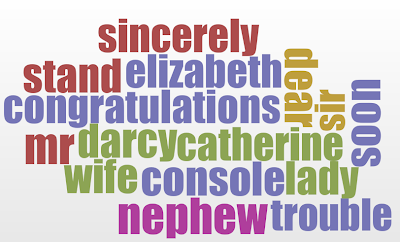

Of all the letters written in the novel, Darcy’s is the only one which demonstrates a major shift in character. Darcy realizes that one of Lizzie’s biggest issues with him lies in the supposed mistreatment of Wickham, so the letter focuses on that particular problem. Darcy himself places a large emphasis on family, though not necessarily seen in his actions, as can be interpreted from the fact that several of the most common words are those relating to family. As such, Darcy would do anything for his family, and anything for his love’s family to keep their standing. Before this moment, Darcy always seems to be haughty and above everyone else. His letter shows that he really wants to explain himself, he wants Lizzy to understand everything behind his motivation and love, and he can’t do that in a conversation. Through all of the consistency in the rest of the letters, this letter and its asymmetry mirror the source of the inconsistency in Lizzy’s life – Darcy himself.

Lizzy generally doesn’t send letters in this book, as her thoughts and feelings are most intimately known through Austen’s commentary. However, Lizzy’s letter sheds an interesting light on her character. Lizzy seems to be one of the most down to earth characters, and yet her major word is “world.” Perhaps she is, in fact, more of a dreamer than we might initially think, and really all she wants is her world to be a dream one. She really feels that she has the best life in the world, after she marries Darcy. As a direct compliment to Darcy’s letter, Lizzy’s shows not how her personality is different in the letter than in her commentary, but how her personality has changed since the beginning of the novel. Of all the letters, this proves to be the most revealing. From the beginning of the novel to Lizzy’s letter at the end, Lizzy develops from a hyper-realistic and cynical person to someone with the capacity to have a hyper-active sense of superlatives. If anything qualifies as fantastic, that had better. Austen uses a few characters with little variation in personality to supplement one girl’s transformation from realistic to less realistic, and people all over the world love her book. What else qualifies as success?

Through the use of letters in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and an analysis by way of word cloud, it can be determined that Austen’s novel does not have a cut-and-dry rule for how letters represent their writers. One thing, however, is definite: those characters who do write letters (with the exception of Darcy) find themselves accurately represented within those letters. Very little core differentiation occurs. Literarily, this represents the consistency in Lizzy’s life gained from her family members, and the resulting instability which entered her life at the same time as Darcy. Darcy changed Elizabeth’s life.

Works Cited

"7 People Who Hated Pride and Prejudice." Mental Floss. N.p., 3 Jan. 2013. Web. 16 Dec. 2013. <http://mentalfloss.com/article/32099/7-people-who-hated-pride-and-prejudice>.

Austen, Jane, and Donald J. Gray. Pride and Prejudice. New York: W.W. Norton, 1993. Print.

"Jane Austen's Art and Her Literary Reputation." Jane Austen's Art and Her Literary Reputation. N.p., n.d. Web. 16 Dec. 2013. <http://www.pemberley.com/janeinfo/janeart.html>.

Showing posts with label awesome. Show all posts

Showing posts with label awesome. Show all posts

Monday, December 16, 2013

Letters and Word Clouds in Pride and Prejudice

Chapter 13, Collins to Mr. Bennet

Clearly, Collins’s main goal in this letter is to show off his newly acquired status – more than introduce himself to the family, he wants to introduce his position to the family, and though he’ll take over the Bennet estate when Lizzie’s father dies, Collins wants to give the daughters a chance to atone for the terrible misfortune of the Bennets’ not having a son.

Chapter 26, Jane to Lizzy

This letter, from Jane to Lizzy, very clearly illustrates the depth of feeling which characterizes Jane. The major words in her letter have to do with a feeling of anxiety, and are often related to her being the older sister, and feeling a measure of responsibility for her family’s and her own situation. She often tries to explain away others’ actions, and see the best in any given situation.

Chapter 35, Darcy's Letter

Darcy realizes that one of Lizzie’s biggest issues with him lies in the supposed mistreatment of Wickham, so the letter focuses on that particular problem. Darcy himself places a large emphasis on family, though not necessarily seen in his actions, as can be interpreted from the fact that several of the most common words are those relating to family. As such, Darcy would do anything for his family, and anything for his love’s family to keep their standing.

Chapter 46, Jane to Lizzy

This letter particularly expresses Jane’s devotion to her family, and their issues, as opposed to just her own feelings in any matter. Notice how none of the major words have anything to do with how Jane herself is faring in light of this matter, but most pertain to other people in the family, or the situation as a whole.

Chapter 46- Jane to Lizzy Number 2

Once again, this sequence of letters has much to do with Jane ensuring that everyone else has what they need, and knows everything going on. Jane once again forgoes telling Lizzy how she (Jane) is, and instead makes sure Lizzy is fully up to speed on the goings-on of the last few days. Everything revolves around everything else for Jane, nothing revolves around Jane herself.

Chapter 47, Lydia to Mrs. Gardiner

Obviously, Lydia does not have the same consciousness for others that her sisters have; the letter mostly revolves around Lydia and what Lydia has done, is doing, and is feeling, and how she thinks everyone else will react to her situation. This is most likely a result of how her mother brought her up – to think of marriage and nothing else.

Chapter 48, Collins to Mr. Bennet

Once again, Collins has demonstrated through his letter that the pompous outside continues on to the inside as well. This time, Collins’s focus leans towards the new acquisition of his wife, and the loss the Bennet daughters have experienced following Elizabeth’s rejection of Collins’s proposal. He becomes extremely patronizing, as the words “dear” and “sir” would suggest.

Chapter 49, Mr. Gardiner to Mr. Bennet

Though we don’t see very much of Mr. Gardiner, the Bennet girls’ uncle, this letter opens up a character who doesn’t say very much in common conversation. Mr. Gardiner seems to be a very family-oriented person, committed to making sure everyone in his family is informed as to the current situation, and safe in any situation which he can control.

Chapter 50, Mr. Gardiner to Mr. Bennet Number 2

Once again, Mr. Gardiner’s rather introverted character is brought to light through his letter to his brother. Mr. Gardiner’s greatest concern in this letter is ensuring that although Lydia may not have married into the best situation, she will have the best possible life out of that situation. This includes Mr. Gardiner doing everything he can to ensure that Wickham’s credit is clean, as the more major words, such as “assurances,” “hope,” and “creditors” would suggest.

Chapter 52, Mrs. Gardiner to Lizzy

Mrs. Gardiner often speaks up more than Mr. Gardiner, and for the most part seems to be a very caring aunt – possibly the one adult female role model in Jane and Lizzy’s lives who cares for their feelings rather than their being married. Her letter surely confirms that her personality in her small words and actions is indeed true. Though Mrs. Gardiner was not supposed to tell of the events that transpired around the time of Lydia’s marriage, she tells Lizzy anyway, just because Mrs. Gardiner knows that Lizzy is extremely eager to know the details, and just how much her family owes Mr. Darcy.

Chapter 60, Lizzy to Mrs. Gardiner

Lizzy generally doesn’t send letters in this book, as her thoughts and feelings are most intimately known through Austen’s commentary. However, this particular letter sheds an interesting light on her character. Lizzy seems to be one of the most down to earth characters, and yet her major word is “world.” Perhaps she is, in fact, more of a dreamer than we might initially think, and really all she wants is her world to be a dream one. She really feels that she has the best life in the world, after she marries Darcy.

Chapter 60, Mr. Bennet to Mr. Collins

This letter sums up Mr. Bennet to a tee. He doesn’t mess around, he likes to be simple and quick, and if he can throw in a little sass somewhere, it’s all for the better. Truly, Mr. Bennet’s transparency stands as one of the most undeniable truths of the novel.

Chapter 61, Lydia to Lizzy

Once again, Lydia demonstrates that her selfishness isn’t purely a surface matter, but a deep characteristic of her most basic form. Even when her older sister is about to me married, Lydia’s letter focuses more on her own life and husband than congratulations for her dear sister.

Clearly, Collins’s main goal in this letter is to show off his newly acquired status – more than introduce himself to the family, he wants to introduce his position to the family, and though he’ll take over the Bennet estate when Lizzie’s father dies, Collins wants to give the daughters a chance to atone for the terrible misfortune of the Bennets’ not having a son.

Chapter 26, Jane to Lizzy

This letter, from Jane to Lizzy, very clearly illustrates the depth of feeling which characterizes Jane. The major words in her letter have to do with a feeling of anxiety, and are often related to her being the older sister, and feeling a measure of responsibility for her family’s and her own situation. She often tries to explain away others’ actions, and see the best in any given situation.

Chapter 35, Darcy's Letter

Darcy realizes that one of Lizzie’s biggest issues with him lies in the supposed mistreatment of Wickham, so the letter focuses on that particular problem. Darcy himself places a large emphasis on family, though not necessarily seen in his actions, as can be interpreted from the fact that several of the most common words are those relating to family. As such, Darcy would do anything for his family, and anything for his love’s family to keep their standing.

Chapter 46, Jane to Lizzy

This letter particularly expresses Jane’s devotion to her family, and their issues, as opposed to just her own feelings in any matter. Notice how none of the major words have anything to do with how Jane herself is faring in light of this matter, but most pertain to other people in the family, or the situation as a whole.

Chapter 46- Jane to Lizzy Number 2

Once again, this sequence of letters has much to do with Jane ensuring that everyone else has what they need, and knows everything going on. Jane once again forgoes telling Lizzy how she (Jane) is, and instead makes sure Lizzy is fully up to speed on the goings-on of the last few days. Everything revolves around everything else for Jane, nothing revolves around Jane herself.

Chapter 47, Lydia to Mrs. Gardiner

Obviously, Lydia does not have the same consciousness for others that her sisters have; the letter mostly revolves around Lydia and what Lydia has done, is doing, and is feeling, and how she thinks everyone else will react to her situation. This is most likely a result of how her mother brought her up – to think of marriage and nothing else.

Chapter 48, Collins to Mr. Bennet

Once again, Collins has demonstrated through his letter that the pompous outside continues on to the inside as well. This time, Collins’s focus leans towards the new acquisition of his wife, and the loss the Bennet daughters have experienced following Elizabeth’s rejection of Collins’s proposal. He becomes extremely patronizing, as the words “dear” and “sir” would suggest.

Chapter 49, Mr. Gardiner to Mr. Bennet

Though we don’t see very much of Mr. Gardiner, the Bennet girls’ uncle, this letter opens up a character who doesn’t say very much in common conversation. Mr. Gardiner seems to be a very family-oriented person, committed to making sure everyone in his family is informed as to the current situation, and safe in any situation which he can control.

Chapter 50, Mr. Gardiner to Mr. Bennet Number 2

Once again, Mr. Gardiner’s rather introverted character is brought to light through his letter to his brother. Mr. Gardiner’s greatest concern in this letter is ensuring that although Lydia may not have married into the best situation, she will have the best possible life out of that situation. This includes Mr. Gardiner doing everything he can to ensure that Wickham’s credit is clean, as the more major words, such as “assurances,” “hope,” and “creditors” would suggest.

Chapter 52, Mrs. Gardiner to Lizzy

Mrs. Gardiner often speaks up more than Mr. Gardiner, and for the most part seems to be a very caring aunt – possibly the one adult female role model in Jane and Lizzy’s lives who cares for their feelings rather than their being married. Her letter surely confirms that her personality in her small words and actions is indeed true. Though Mrs. Gardiner was not supposed to tell of the events that transpired around the time of Lydia’s marriage, she tells Lizzy anyway, just because Mrs. Gardiner knows that Lizzy is extremely eager to know the details, and just how much her family owes Mr. Darcy.

Chapter 60, Lizzy to Mrs. Gardiner

Lizzy generally doesn’t send letters in this book, as her thoughts and feelings are most intimately known through Austen’s commentary. However, this particular letter sheds an interesting light on her character. Lizzy seems to be one of the most down to earth characters, and yet her major word is “world.” Perhaps she is, in fact, more of a dreamer than we might initially think, and really all she wants is her world to be a dream one. She really feels that she has the best life in the world, after she marries Darcy.

Chapter 60, Mr. Bennet to Mr. Collins

This letter sums up Mr. Bennet to a tee. He doesn’t mess around, he likes to be simple and quick, and if he can throw in a little sass somewhere, it’s all for the better. Truly, Mr. Bennet’s transparency stands as one of the most undeniable truths of the novel.

Chapter 61, Lydia to Lizzy

Once again, Lydia demonstrates that her selfishness isn’t purely a surface matter, but a deep characteristic of her most basic form. Even when her older sister is about to me married, Lydia’s letter focuses more on her own life and husband than congratulations for her dear sister.

Thursday, November 21, 2013

"The Rime of the Ancient Mariner" and its Ties to Lucifer

We spent Wednesday in class talking about the poem “The Rime

of the Ancient Mariner” by Samuel Coleridge, and after the class discussion I

spent a lot of time thinking about it. After some careful consideration and

re-reading the poem, I came to a rather interesting conclusion.

Throughout the poem, the action seems to bounce between good

and evil, the Mariner never sure exactly which side he lies on. The very

beginning of the Mariner’s story talks about the beauty of the sun, how “he

shone bright,” for all the men on his ship (378). However, the story takes a

dark turn when the Mariner shoots and kills a good omen, the albatross.

I would submit that the entire first half of the poem, if

not the whole thing, is a telling of Lucifer’s fall, and God’s punishment

afterwards. Now, going on this analysis there are two distinct alternatives for

how the telling plays out. The first option is that the Albatross represents Lucifer,

and the Mariner represents God; shooting the albatross with the crossbow is a

physical representation of the angel Lucifer falling from grace, and his

punishment is to not be present in the world to see humanity take its shape.

While this is a very good argument, I’m much more partial to the second option.

The second (and more probable) option is that the Mariner is Lucifer, and the

Albatross a representation of God. The mariner, “with [his] crossbow” shoots

the Albatross from the sky, killing it (380). The use of a crossbow in killing

the Albatross is instrumental, because of its relationship with the cross.

Lucifer, when he was cast to Hell, believed he fell because he loved God too

much. The Mariner kills the physical representation of God with an item of

significant religious imagery, physically demonstrating Lucifer’s overwhelming

love for his Father, so much so that it hurts God.

Moreover, when the Mariner thinks all is lost, and he’ll

never find home, he sees life, and says:

“Beyond the shadow of the ship,

I watched the water-snakes:

They moved in tracks of shining white,

And when they reared, the elfish light

Fell off in hoary flakes.

Within the shadow of the ship

I watched their rich attire:

Blue, glossy green, and velvet black,

They coiled and swam; and every track

Was a flash of golden fire” (386).

That the Mariner welcomes the

snakes and fire is no hallucination, or “just happy to see something” attitude.

In essence, this can be seen as Lucifer accepting his place in Hell, and

welcoming the gates to him, because

he realizes that his power is indeed great enough to bring the gates of Hell to

him. The Mariner delights in seeing these signs of evil, instead of cowering

away, which greatly supports the hypothesis that the Mariner represents

Lucifer, and the poem is a loose telling of his fall from grace.

Furthermore, the Mariner’s ultimate

fate is to live in agony, so people know his story. He says, “That agony

returns:/ And till my ghastly take is told,/ This heart within me burns” (396).

This, really, would be Lucifer’s Hell on Earth. Rather than being allowed to

rule his domain in Hell, no matter how dislikeable that really is, God forces Lucifer

to live on the planet among those whom he refused to love in the first place

(Lucifer told God that he could not love man more than God because they were

violent creatures who didn’t deserve the love Lucifer had to give), and teach

them of his Father, try to make them see why God is great. Because, Lucifer

believes he still loves God, that God is great no matter the situation, or what

he did to Lucifer. The Mariner even says, “For the dear God who loveth us,/ He

made and loveth all” (397). Even in his greatest punishment, Lucifer sees how

much God loves, and yet still refuses to love humanity with all the strength

and conviction with which he loved God, and that is why he is doomed to his

Hell, teaching those he hates about God and his love.

In a nutshell: the mariner is

Lucifer (not Satan/the Devil, but Lucifer. Important distinction, because

Lucifer is the archangel that fell from grace, Satan and Devil are the names we

give to him to embody the evil we believe is in his soul) and the Albatross a

physical representation of Lucifer’s betrayal of God and fall from grace.

Friday, November 15, 2013

Revisiting Brave New World

In my last blog, I talked about Huxley’s persuading that

individual thought is like a cancer for the proverbial “social body” of Brave New World. In this post, I’d take

that both forwards and backwards, and propose that Huxley persuades not that

individual thought acts as this cancer, but individuality in a much broader

sense. Additionally, the social body of the World State must do whatever is required

to ensure the survival of the body.

The Director most adequately describes the danger to the World

State which comes from individuality, stating, “’Unorthodoxy threatens more

than the life of a mere individual; it strikes at society itself’” (137). Most

slyly, Huxley places in the metaphor of the snake, in saying that unorthodoxy “strikes”

society. This metaphor plays a key role in the understanding of how much this

society relies upon uniformity. The proverbial snake of individuality can, at

times, slither in unnoticed, and wreak havoc on the World State, first causing

the body to panic, then, if the snake is allowed to “bite” the metaphorical

body, causing widespread damage. Because of the immense danger individuality

poses to the society as a whole.

Due to the danger associated with individuality, those in power

within this society must act quickly and swiftly to remove anyone whose

independence of thought and action may pose a threat to the stability of the

society. Because of this, the Director quickly acts when he sees Bernard

becoming too independent, and states that “’In Iceland he will have small

opportunity to lead others astray by his unfordly example”’ (139). Bernard’s

punishment is to be removed, so much like the cancer he could be to this social

body, and placed somewhere else, in a sterile container full of others like

him, where the cancer can’t spread to “civilized” society. That society removes

Bernard as opposed to just killing him says a lot – the stability is so

fragile, they have to make everything seem well and good for the lower castes,

going to Iceland to them just seems like a change of location, not the

punishment it’s intended to be. They must, at all costs, maintain the outward

appearance of being completely stable in ideals and the human makeup of the

upper division of humanity, lest the lower division become restless and follow

those with ideas contrary to the hypnopædic teachings of the Conditioning Centre.

Truly, the rights of the individual fall under the pressure

to keep society stable, which the Director most adequately describes when he

says “’It is better one should suffer than that many should be corrupted’” (137).

More than characterizing the mindset of the Director, this statement

characterizes the society as a whole. Where, especially in our society, the “one”

has a high value, especially for those close to the proverbial “one,” this

society places stability of the many above the comfort and wellbeing of any one

person, or even a small group of individuals, those with differing viewpoints

are treated as well as any malignant cancer can be expected to be treated - - with

hostility and the intent to remove the tumor as quickly and efficiently as

possible. For Linda, the doctors let her drug herself to death on soma, for Helmholtz and Bernard, those

in charge shipped them away, to a place where others like them lived, but couldn’t

touch the social body.

Truly, more than anything else, this society focuses on

smashing down individuality, and making the overall body of people as much like

one continuous person as possible. From the very beginning, this is so. The

lower castes are made up of so many identical people, hundreds upon hundreds

genetically identical, and thousands upon thousands genetically related. Then,

all people from each caste are engineered mentally, to have the same thought

processes, the same intellectual identity. And, finally, they take away the

intellectual free time of each individual in the society, balancing just enough

work with just enough play, supplementing that play with soma, so no one has the time or forethought to really even think

about why society acts the way it does, or who they are individually. Most

certainly, Huxley aims to point out how each individual truly is just a cell in

the body, and those with the mentality and thought to act as individuals are

the better off for it. They are sent to places where other like them exist,

where intellectuality and thought and creativity exist, and where they can be

themselves, free of the rigorous hypnopædia and conditioning which takes away

the beauty from the world, and replaces it with infantile gratification,

instant happiness, and general stagnancy of being. (774 words)

Thursday, November 7, 2013

A Touch of Cancer

Thus far into A Brave

New World, major themes are as yet still building, and for the most part

the key to the novel has remained elusive. However, the novel seems to be

highly interested in the negativity of individuality and personal identity. Social

continuity and homogeneity maintain themselves as society’s stability, and

individuality threatens the entity which is this World State.

The first instance which begins to explore the instrumentality

of stripping society of individuality comes in the very beginning of the novel,

when the students tour the Central London Hatchery and Conditioning Centre. The

new process for fertilizing eggs and then making embryos results in, for all

castes other than Alphas and Betas, results in “Making ninety-six human beings

grow where only one grew before. Progress” (Huxley 17). Syntactically, these

statements represent much of the philosophy of the society. It (the society)

does not need to be made up of “complete” individuals, ones with independent

mindsets, goals, and outlooks on life. Like these near-sentences, the people of

the society can carry out their function without having a full consciousness. This

encourages the retraction of individuality, and substitution with hive-minded

people, for the sake of a more efficient system. Much like the way Huxley uses

only fragments to describe the lack of genetic individuality within the World

State, the geneticists and breeders strip the people down to only the necessary

elements for their castes. Intelligence, psychological preferences and

predispositions, and social mindset are precisely engineered to ensure the

human contains only what is exactly necessary to give meaning to the situation,

but not enough for any extraneous meanings or opinions to form from the

information planted in that person.

Because the society actively puts down individuality, any

appearance of difference is heavily ridiculed. Even the individual who appears

or thinks differently than the rest of the society notices the difference, and

extreme self-consciousness of the difference results. Bernard Marx, while

intellectually equal to anyone else of the Alpha-Plus caste, is slightly

shorter than the rest of his caste, and as such feels out of place. Because of

this difference, “feeling an outsider he behaved like one,” directly characterizing

Marx as someone in direct conflict with the goal of the World State society

(69). In the case of the type of characterization Huxley employs to expose

Marx, the use of direct as opposed to indirect characterization supersedes the

importance of the explicit word choice of the statement. Though the others of

his caste and his general society have an awareness of the difference between

Marx and others conditionately equal to him, Marx has the greatest awareness of this difference. Marx internalizes his

difference from others, and even works to make it larger. He consciously

separates himself from the rigorous hypnopædia propaganda he was exposed to as

a child. He wants to get to know the women he sees, as opposed to having lots

of one night stands. His interests directly conflict with the society, and when

people see this, they look down on him, more so than they do simply because of

his physical “defect,” as it were. Any form of individuality maintains itself

as alien to this society.

Furthermore, this individuality greatly threatens the

society as a whole, whether Marx knows it or not. The society as a whole cannot

function properly if a member becomes different enough to challenge the norms,

although, as the Director states, “the social body persists although the

component cells may change” (95). Marx’s mentality and challenging of the norms

and hypnopædia represents something far more dangerous than simply a component

cell dying and being exchanged in the metaphorical body of the World State.

Newness of thought, innovation of opinion and tradition have the potential to

spread like a cancer through this society, destroying it from the inside.

Truly, the most dangerous occurrence for this society lies in the possibility

that hypnopædia could be overcome, and the past freedom of thought come back.

Especially dangerous, because the only people physically capable of this kind

of thought are in the upper castes, and as a result, the differences in thought

would manifest in the most important parts of the proverbial body, the

reproductive system, the brain, the vital organs. A cancer of the support

system of the body, the lower castes that keep the infrastructure going, a bone

or skin cancer that is slow growing and not quick to metastasize, that can be

cut out, cut off, and the body can keep going. But, when a cell in the brain,

in the heart, in the major systems of the body becomes cancerous and begins to

spread and grow, to overtake the mother organ and then move to others, it takes

down the whole body, cannot be removed because as surely as the cancer will

kill the body, so would the surgery necessary to remove it. This cancer is

fatal. Huxley points out that even when highly conditioned, individuality, social

cancerousness exists; to a society completely reliant on uniformity and the

stripping of individual identity, the danger this cancer poses is real, and

could spread to Stage IV before the body even realizes it’s there. (859 words)

Wednesday, October 16, 2013

Misery in Marriage

Today in class, a certain question was raised about a

certain someone being happy in her marriage to Mr. Collins. I intend to answer

the question with the utmost clarity and decisiveness.

I’m going to make this perfectly clear: the word “happiness” does not

apply in any way, shape, or form, at any point in time, to Charlotte after she marries

Mr. Collins. In fact, a better word to describe the Collins’ marriage

would fall more under the scope of absolute misery.

Let’s begin with the object of Charlotte’s eternal misery,

Mr. Collins. From the very outset of the

engagement (not the marriage, the engagement), Charlotte demonstrates that

she clearly understands the horrific entity that is Mr. Collins. In a rather

colorful demonstration of indirect characterization on Austen’s part, Charlotte

describes Collins as “neither sensible nor agreeable, his society was irksome,

and his attachment to her must be imaginary” (Austen 83). As almost all

negative commentary on Collins’s personality comes from indirect

characterization, everyone but

Collins knows that he’s basically the single person that no one wants to be

around (with the exception of Lady Catherine). Charlotte’s certainly not a fan,

and she knows that part of Collins’s interest in her is due to the fact that he

wants to get back at Lizzy. Charlotte doesn’t

even care. All she wants is to be secure in life, happiness was never part

of the equation. She willingly sacrifices her happiness to be a part of Collins’s

game with Lizzy.

With the event of her marriage, Charlotte’s potential

happiness takes a downward turn, as Elizabeth observes during her visit to Rosings

Park. When Collins talks about working in his garden, “Charlotte talked of the

healthfulness of the exercise, and owned she encouraged it as much as possible”

(104). So, basically, Charlotte does everything she can to kick Collins out of

the house so she can have time to herself. She desperately needs an escape. Charlotte

and Collins have been married less than six months at this point in the novel,

and already Charlotte does everything she can to escape the union (barring

actual divorce. This is the late 18th century, divorce is still a

no-no, and only possible under certain very explicit situations. See this

link if you wish to learn more). Though she thought she was prepared for a

loveless marriage, one that might potentially grow love in the future, Charlotte

clearly underestimated the supreme awfulness of the situation at hand. Society

never taught her how to handle something of this nature, so she runs away from it.

Moreover, she has to deal with Lady Catherine, arguably one

of the most intolerable women of any fictional era, and, coincidentally, a

historical allusion to Catherine the Great of Russia. Catherine the Great,

though very powerful and well-known, was not often well-liked. In fact, she had

a small circle of people who liked her very much, and a large conglomeration of

people who didn’t like her at all. Lady Catherine de Bourgh intentionally

mirrors her historical predecessor to the very last, to emphasize the utter

misery in which Charlotte must spend the rest of her life. One night when

playing cards after dinner, “Lady Catherine was generally speaking – stating the

mistakes of the three others or relating some anecdote of herself” (111). This

represents Lady Catherine de Bourgh’s general action and attitude. She’s

self-important and haughty, and the only person who likes her is Collins (that’s

her “small circle” which parallels that of Catherine the Great). Pretty much

everyone else can’t stand her, but they’re nice to her because she has money. Charlotte

has to deal with this woman at least once

weekly, sometimes more if Lady Catherine is feeling condescending and ambivalent

enough. That alone in and of itself would be enough to make any person with

half a rational brain – which Charlotte most certainly has – miserable for all

of eternity. Out of propriety, society requires Charlotte to interact with the

woman and seem as if she likes Lady Catherine, but, in reality, the woman is

completely intolerable.

In conclusion, security

and happiness are very different

concepts. While Charlotte has the money and stability she wanted, she doesn’t

have anything to facilitate a feeling of happiness or felicity. Her husband,

from the very beginning, isn’t described as an agreeable person. Charlotte has

to actively work to get almost-happy time to herself, and is constantly

confronted with a nasty woman who adamantly feels the need to criticize

everything everyone else round her does and says. These are not the elements of

a happy marriage, or even a happy life situation. Charlotte is secure, not happy. These are two completely different ideas, of which only one

can apply to the new Mrs. Collins.

Friday, October 11, 2013

Society - The Monster or the Master?

The late and great Jane Austen penned many an insightful,

witty novel, perhaps none more insightful and witty than the classic Pride and Prejudice. While some might

deign to say that it’s just another trashy romance, in reality it combines

humour, high society, and relationships into a tightly-packed, socially

relevant novel about the trials and tribulations of growing up as a woman during

the transition from the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries.

Perhaps one of the most important and relevant messages in Pride and Prejudice – even for today’s

audience – lies in that a person (particularly a woman) must choose to be

active in her life, and not allow the constraints of society and money to shape

her expectations of life and herself. This especially comes through in the very

evident juxtaposition between Charlotte and Elizabeth. Both of these women want

to be secure in later life, but each takes a surprisingly different approach to

gaining this security. In fact, both women have very different definitions of what security means.

Austen’s message most prominently

comes to light in the two girls’ reactions to Mr. Collins. Charlotte very

clearly states that, “Marriage had always been her object, it was the only

honourable provision for well-educated women of small fortune” (Austen 83). At

twenty seven years old, Charlotte literally does

not care. She simply requires a reasonably well-matched marriage; the

feelings, specific situation, and other details are of absolutely no

consequence to her. Charlotte absolutely conforms to society. Elizabeth, on the

other hand, refuses to allow society’s design to shape her life. Upon Collins

proposing to her, Elizabeth exclaims, “You could not make me happy,” clearly articulating that, contrary to Charlotte’s idea

of security, Elizabeth believes security to lie in happiness rather than

monetary value and comfort (73). More than juxtaposing only Charlotte,

Elizabeth juxtaposes all of English

society. Austen essentially employs Elizabeth as one huge slap in the face

for English society, stating that a woman should have (and does have) the power to choose a partner for love over money, in

the same way that a man can. Austen uses this juxtaposition to articulate that

although the everywoman (Charlotte) will consistently follow society, there is another way (Elizabeth).

Clearly, both of these women want

the same result out of life – some form of security. However, the word “security”

emanates different meanings for each. Charlotte rides with the generally

accepted, socially farmed-out meaning: a comfortable income and husband who can

provide said income = security. Elizabeth, the rebel child, takes a completely

different road. For her, security begins

with love, none of this “the love will grow from the relationship” crap that

people who arrange marriages have been spouting since the beginning of time.

The money, for Elizabeth, grows (hopefully) secondary to picking the right man

to love. She refuses to be unhappy in a societally secure relationship over

being happy in a possibly less wealthy situation.

Moreover, even each woman’s

situation seems to grow into a juxtaposition of the other’s, after Charlotte’s

marriage to Collins. When Elizabeth observes Charlotte’s air when Mr. Collins

is not present in their home she notices that, “When Mr. Collins could be

forgotten, there was really a great air of comfort throughout” (105). Clearly,

Charlotte does not find any happiness in her current situation. Had she felt

any positive feelings at all for her marriage (above convenience and relief), Charlotte

might endeavor to be slightly closer to her new husband, as a newlywed and all.

However, she actually does her best to get him out of the house, forget about

him, and go about her own work! Following society’s guidelines becomes one of

the least emotionally rewarding decisions Charlotte makes, and she has no

choice but to live in this discomfort for the rest of her life. Elizabeth,

however, finds herself enjoying life after she rejects Collins. She finds

herself often fraternizing with Mr. Wickham, and openly admits “Mr. Wickham’s

society was of material service in dispelling the gloom,” which arose from the

departure of Bingley and his family from Netherfield, in addition to recent events

with Collins (93). Lizzy quickly moves on with her life, and her decision to

flaunt authority and go against society has, thus far, worked very well for her. Austen demonstrates that

sometimes, though it may seem wrong to go against society, defying society comes

out with the best individual results.

And, to conclude, isn’t the individual result more important than

the conglomerate result which society desires? The fact is, not all the women

in a society can hope to marry up and have comfortable livings in nice parishes

where stuck up rich women tell those young ladies how to properly arrange their

living room furniture. There simply aren’t enough good, rich men for that. So,

instead, Austen proposes that a better way to gain happiness and security in

life is to do something that makes you happy, rather than trying something

which society dictates you should

try, in the minute hope that maybe everything turns out okay.

Monday, August 26, 2013

NEW THEME!!!

So, I am aware that this blog was once for CAS-oriented, IB things. However, I need to use a blog for my Masterpieces of British Literature class, and I was decidedly too lazy and non-creative to come up with a new blog, so I will now be re-naming this blog and using it for whatever I choose, including (but not limited to) posts for my lit class :) Stay tuned for the first of many posts about British awesomeness!!!!!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)